FRECKLES: A HISTORY

Photographer Richard Phibbs captures the unique beauty of dappled skin, while cultural curator Sarah Forbes explores the anthropology of freckles.

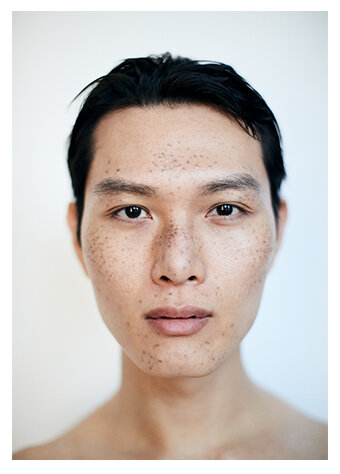

“I grew up in Taiwan and have some features most Asian people consider ‘not beautiful’ . . .big cheekbones, a square jaw, freckles, femininity. Studying fashion and living in London really opened up my mind about beauty and not needing to follow mainstream aesthetics.”

–PACE

THE CONSTELLATION ACROSS my face, my freckles, or—as my mother would call them—my “sprinkles of cinnamon,” are both the visual story of who I am (my genetics) and where I’ve been (38 years of sun- kissed adventures). Those little dots that intensify or fade across the seasons, and for some, come, go, and return across our years are visual secret keepers of everything that makes us freckled people who we are.

Freckles conjure a collective visual archetype: a bespeckled, milky complexion and a cheeky redhead, backdropped by the verdant Irish countryside. Be honest, isn’t that the image that first popped into your mind? While Northern Europe predominates in its abundance of redheads, with Scotland and Ireland said to have about 10 percent of their populations with the flame, “gingers” make up only approximately 2 percent of the global population. This rarity has fueled the world’s curiosities and fears across history: Are red- heads magical beings, stronger and healthier than most, an evolutionary catapult in vitamin D production? Or are they malign creatures, even suspected of being witches during some particularly unaccepting times (there was also a bit of anti-Semitism here, as red hair was in certain historical moments linked to Judaism). And if it wasn’t just the hair color that set them apart as either a talisman or a curse, nature doubled down and gave a good percentage of them freckles.

“My freckles to me are one of the most interesting things about my appearance, and to me they symbolize the strength and beauty of my hometown in Georgia and remind me of my roots as a southern girl being out in the sun. I’ve had a love/hate relationship with them growing up, but I know their value now as a feature that is uniquely me.”

–LAUREN

Scientists will now tell us red hair and freckles are linked to the MC1R gene, which is essentially the color director of our proteins and decides what kind of melanin will be produced from two possibilities: eumelanin (dark brown and more common) and pheomelanin (reddish yellow). An inactive MC1R gene, or one that is not working, allows for the increased production and build up of pheomelanin, linked to light hair, skin and wait for it . . . freckles. Emerging in a multitude of varieties, freckles can either be dermatologically classified as ephelides, 1 to 2 millimeters in size, or their big sisters, lengtigines, weighing in at 1 to 2 centimeters in diameter. While red hair is genetically recessive, interestingly, freckles are genetically dominant, leading to their representation on a wide palette of hair and skin combinations.

“Unity makes me feel beautiful. Picking others up when they feel down makes me feel beautiful. Acts of charity make me feel beautiful. Ultimately, making others feel beautiful makes me feel beautiful.”

–NICOLE

And this is the atypical category I fall into . . . you see, I’m not your average redhead, with my dark auburn wavy locks, once the color of deep copper pennies when I was a child, a color so unusual people on the street would ask for a lock to take to the hairdresser for color matching. My skin is not fair like my mother’s, a compliment to her green eyes and her (no other way of describing it) fire-engine-red hair. A genetic telltale of her Russian ancestry and maybe a potential link to the Udmurt people there, who are said to have the “reddest hair in the world.”

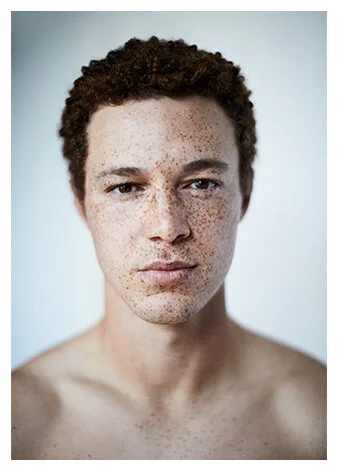

“My freckles and curls make me feel beautiful because they signify my individuality and uniqueness.”

–DUSTIN

Though my cheeks are sprinkled with freckles, which also oddly congregate en masse on my elbows and knees, in reality I take much of my coloring from my Mexican-American father in both the darkness of his eyes and my ability to tan to the color of a rusty desert, making the inhabitants of most sun-filled countries believe I am one of their own. In a time before we lathered our children with the highest factor sun products possible, my mother—who worshiped at the altar of 1970s disco glamour and the chic cachet of being bronzed—thought it was enviable how easily I toasted in the Arizona sun of my childhood. Genetically and culturally, freckles were my destiny.

So while our genes will make us more or less predisposed to freckles––and it’s interesting to note that in Chinese populations a gene other than MC1R controls freckling––ultimately, the manifestation of freckles will come down to our individual sun exposure. More than just an affront to our contemporary anti-aging regimes, historically our sun exposure has said a lot about our individual socioeconomic status. In centuries past, during which agricultural work dominated, sun exposure was a quick clue as to who was out in the fields and who was calling the orders from the shaded veranda.

“My freckles tell the story of my life—the summers I spent going to the community pools in Arizona, the time I sailed around the Amalfi coast, the melasma my daughter gave me…I’m proud of the skin I inherited from my mother.”

–RACHEL

While we are all aware of the deeply racialized history of this in regards to African American slavery and colonization on plantations across the world, very little has been discussed on the relationship and significance of freckles and, by extension, the commercial market based on their removal in Caucasian populations. We “freckle-face strawberries,” à la Julianne Moore’s children’s stories, have been told through so many angles of society that these marks are antithetical to beauty. But how and why was this decided?

As a child I used to cry about my freckles, begging unsuccessfully for my mother to buy me any number of magic creams to bleach them away. Only later would I academically understand these creams as tied to the commercialization of the cultural valuation of white skin (minus sun exposure). As a little kid, I didn’t know that 19th-century women were so eager to whiten their skin that they purchased “Dr. James P. Campbell’s Safe Arsenic Complexion Wafers”––and yes, people knew arsenic was a deadly poison at the time. Or that at the turn of the 20th century the market was saturated with products such as “Stillman’s Freckle Cream,” which still exists today, though now sold predominately to women in India looking for lighter complexions.

“Standing out in a crowd of people makes me feel special. Walking into a room with a couple of my friends, and I’m the first one being looked at, really gives me the sense of being beautiful, of being a limited edition, one-of-a kind rarity.”

-SHELDON

As a little kid I didn’t know the history of derogatory words such as “redneck,” indicating a white laborer who spent their time in the sun. I didn’t understand the economic and racial battle that took place between typically white itinerant American farmers (who probably not too many generations back came over from Northern Europe) and enslaved Africans, who had no say over every factor of their new existence. Light, unfreckled skin, became a status marker.

That is, until the world began to associate a suntan with the ability to “summer” and purchase “cruise wear” for travel to exotic and luxurious locales. A suntan became the marker of being able to not only afford the vacation but also the time not working. By the 1990s, supermodels sported their freckles with honor, as if they were donning the latest fashion trend. Freckles became “youthful” and “glowing,” with the first faux freckle products from distributors such as Chanel, sold to us, in the same way freckle-removing creams were previously.

“My freckles were something I developed over time. I haven’t always had as many in density as I do now, so they were a

challenge to accept at first, but now I’ve conquered all struggles of thought and see them as something that has made me stronger in a way that no matter the shock some people may feel in seeing my face, I’m able to calmly accept others disapproval, approval, or indifference.”

–KOKIE

As a mixed kid, this ability to tan as well as to freckle has been a visual manifestation of my relationship with a confusing identity. As I entered young adulthood, armed with these historic foundations, I began to find pride in my freckles . . . something that made me feel identified with all the other mixed kids. Without any kind of scientific foundation, only an emotional one, freckles felt like the emblem of our tribe. It brought me the joy of a little kid when Meghan Markle told off editors for photoshopping away her royal freckles. As an adult, I now keep my face foundation free, flying the uneven-melanin flag with pride.

As an anthropologist ever-fascinated in the story of humankind––one who has had a unique, if not unprec- edented, view into sex, attraction, and festishization as the curator of the Museum of Sex for more than a decade––I see my freckles as so many things now:

a crazy cocktail of my genetics and sun exposure. As I reached my own sexual maturation I saw how my freckles went from “adorable” to, for some people, a serious kink or fetish, though I wouldn’t say this was the case for my Dublin-born-and-raised husband, who jokes he married me in spite of dark red hair and freckles. Oh, Irish humor . . .

“My freckles are my cinnamon sprinkles. They mean I have a little spice. I feel most beautiful when people make me smile… and also when I drink champagne. “

–HELEN

There is a little-known Irish legend in which the Gaels tells the gods about their island, which they feared they would not be able to return to, unable to see the stars for navigation through a heavy mist. One of the gods tells the Gaels: “Behold, I will draw on you a map of the Universe, so that you will remember us in the dark nights when you cannot see the stars because of the mist which covers your small island.” The god then sprinkles a fine dust over the Gaels, which covers them in freckles. The freckles are called briciní, which means “little stars” in Irish. Who knew I had a map to the universe dotted across my skin?

I may not be Irish, but I do think us freckle- faces are magical.

Dubbed a “sexpert supreme” by Cosmopolitan, SARAH FORBES is a curator, sexual culturalist, and personal ethnographer. Her memoir, Sex in the Museum, is based on her decade as the curator of the Museum of Sex. The founder of Citizen Curated, a personal history and estate planning service, Sarah is also writing her second book, Mama Sex, an anthropological look at motherhood and sexuality.